Manorialism, or the Manor System, was a key component of Feudalism in Western Europe in the Medieval Era. Sometimes known as the Middle Ages, this period lasted from shortly after the end of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE and the Renaissance in the late 15th century. In this article, we’re going to answer what Manorialism and what its impact was.

What is Manorialism?

At the most basic level, Manorialism refers to the organization of the economy under Feudalism. Because agriculture was the dominant industry, it defined who owned and made money off the land.

Typically, a feudal lord lived in a manor with attached farms, villages, and woodlands. Serfs, or villein, lived in the surrounding area as the lord’s tenants. The primary purpose of Manorialism was to organize rural societies into small functioning units.

Some people confuse it with Feudalism because they’re so intertwined. The best way to think of the difference is that Feudalism was a political system, and Manorialism was an economic system. Feudalism was concerned with the legal relationship between peasants, knights, nobles, kings, and the church.

The Manor System’s roots come from the late Roman Empire’s villa system. As the birthrate declined and labor became more crucial and in-demand for agriculture, the empire’s solution was to freeze the social structure. If your parents were farmers, you were going to be a farmer as well.

As Roman authority crumbled and Germanic kingdoms invaded, they took over the Roman Landlords’ holdings, keeping the same policies in place. The chaos at the end of the empire and the Arab conquests disrupting trade in the Mediterranean forced the Medieval economy further towards agriculture.

How Did The Manor System Work?

To start, a lord received land from a higher-ranking nobleman or king, which was his manor. With the land’s gift, he also had the right to everything on it, including the people. The peasants either paid the lord or directly worked for him. In return, the lord ran a court and protected those living on his land. It was the extreme decentralization of government, creating thousands of mostly autonomous units within a larger kingdom.

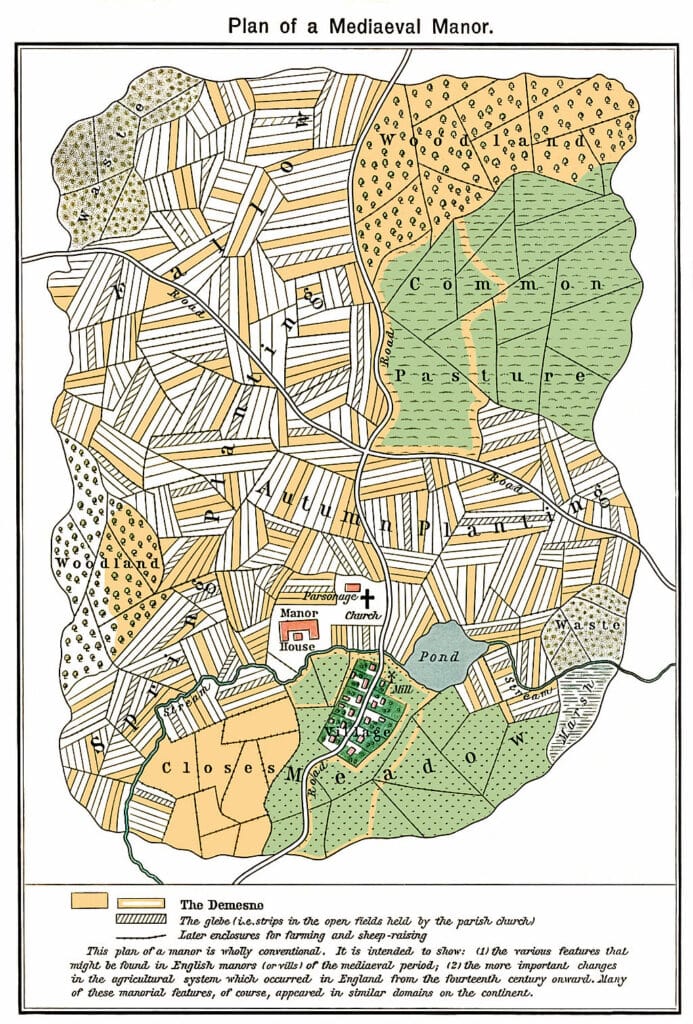

The manor consisted of three types of land:

- Demesne: The lord directly controls this land. Everything it creates goes straight to the lord and his household.

- Dependent: The serfs or peasants work this land without oversight from the lord, but they owe either labor on the Demesne or a portion of goods created. These lands are hereditary, with the tenants paying a fee every time it passes from person to person.

- Free land: This land was ruled by the manor but not subject to labor or an output tax. Usually, peasants would pay a larger upfront fee to rent this land.

Under Manorialism the “manor,” or lord’s residence, is the central point of everything. You might think of famous medieval castles when you picture a famous feudal castle-like Leeds Castle, but that wasn’t typical. Only very wealthy feudal lords had manors like that. Instead, many manors were a more straightforward structure made out of wood and stone. Just because they were simpler didn’t mean they weren’t excellent. A manor was far better maintained than any of the housing around it.

The manor usually included things like a bakery and mill, which peasants would pay fees to use. Even the legal system was fee-based, as peasants paid to have their disputes settled by their lord.

Though peasants lacked a lot of rights, they weren’t slaves, as many people believe. They had legal rights through the court, and they could technically leave their land, though they’d likely starve to death if they did.

A portion of fees a lord made would get paid to higher lords or the monarchy. To put Manorialism in modern terms, it’s similar to MLMs or pyramid schemes. Those at the bottom struggled, while those further up the pyramid thrived at their expense.

How did Manorialism end?

In the summer of 1347, Genoese traders fled a Mongol siege in Kaffa for Constantinople, bringing the bubonic plague with them.

Europe was entirely unprepared for its arrival. Hygiene was virtually non-existent, and within decades, one-third of Europe’s population was dead.

Peasants left when outbreaks came, creating a mobile for the first time in centuries. When combined with the number of people who died, this drove the value of labor up. Peasants wanted better conditions and more economic power, and the lords had to concede. Eventually, this gave way to mercantilism and capitalism, ending Manorialism’s hold on Western Europe.

- Tulip Mania – The Story of One of History’s Worst Financial Bubbles - May 15, 2022

- The True Story of Rapunzel - February 22, 2022

- The Blue Fugates: A Kentucky Family Born with Blue Skin - August 17, 2021