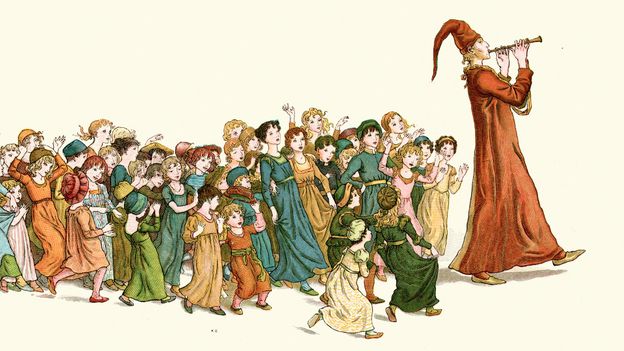

Every school child is familiar with the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin, or at least the vague elements. It involves a mysterious figure showing up in a town in Germany during the Middle Ages, both scaring away a plague of rats from the settlement and then luring scores of children away from the town.

It has been retold in many incarnations, particularly since the early nineteenth century when a great interest developed in German and Nordic folklore tales throughout Europe.

But the question is; what is the actual back story to the tale of the Pied Piper, and was it based on any events which actually occurred in the town of Hamelin in the Late Medieval period?

Here we look at the facts.

The Original Story of the Pied Piper

Let’s start with the story itself, or perhaps we might more accurately refer to it as a fable or at least an allegorical tale. It takes place in 1284 in the town of Hamelin or Hameln in Lower Saxony in north-western Germany.

This century was a period of immense social and economic change in Germany. Central Europe moved from being the frontier of Christendom, bordering huge areas of Pagan settlement in northern and eastern Europe, to one more central.

It also prospered enormously as the Hanseatic League, a broad alliance of trading partners based out of northern European towns, expanded its trade networks throughout the Baltic Sea and North Atlantic.

In this world, the Pied Piper appeared at Hamelin in 1284. According to legend, the town was suffering from a rat infestation.

The Piper of lore was a man hired to deal with the problem, and he was given the ‘Pied’ description because he dressed in multi-colored clothing.

He promised the Mayor of Hamelin that he would get rid of the rat infestation in return for 1,000 guilders, a very handsome reward if he could manage the feat.

And the Pied Piper succeeded. He played his pipes and lured the rats out of the town and into the local River Weser, where they all drowned. But then a problem arose.

Having succeeded in his task, the mayor refused to pay the Piper, offering him a tokenistic sum of just 50 guilders. Infuriated, the Piper is said to have now determined to steal away the town’s children in revenge. T

Typically this is said to have occurred on the Feast of St John and St Paul on the 26th of June 1284, and that the Piper, returning to the town, dressed now all in green, lured off 130 children from the town of Hamelin.

The Piper then led them into a local cave, and they were never seen again, though other versions depict the Piper as directing the children to a hill where they were entranced into plummeting off of it to their deaths. Such was the tragedy of what happened with the Pied Piper and the children he led away from Hamelin.

What Really Happened in Hamelin?

Now, was any of this true? It would be easy to dismiss this as a complete myth. But research across the twentieth and early twenty-first century has produced several plausible theories for how this might have corresponded to some actual events at the town of Hamelin in the late thirteenth century. Some are less believable than others.

For instance, it has been suggested that the disappearance of the children from the town might be linked to a form of mass psychogenic illness, one which created a dancing mania amongst the children.

Contemporary records attest to such outbreaks of mass mania in Germany during the thirteenth century, so as unlikely as this scenario seems, it is still possible.

Another theory is that the children were recruited to join a new crusade to the Holy Land, which had been ongoing since the late eleventh century. And yet another theory posits that the Pied Piper is a symbolic character used as a symbol for the outbreak of the bubonic plague in the town of Hamelin, or some other severe disease, one that killed most of the town’s children.

In this view, the Pied Piper of Hamelin myth was invented to explain away the townspeople’s grief concerning a disease that they could not understand, explain or fight.

However, one other explanation presents itself as the most likely. As we have seen, northern Germany and the lands further to the east into Poland were at the frontier of European Christendom in the Late Medieval period.

Parts of Europe around the Baltic Sea area of Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia had only recently been Christianised by settling communities of Christian settlers from Central Europe in these regions.

As part of this colonization drive, individuals known as lokators were sent around thirteenth-century Germany to recruit large numbers of individuals who would move out to Eastern Europe to aid in the Christianisation of these lands.

Generally speaking, young people, where the males could act as soldiers and start families out in the Baltic Sea region, were favored.

Therefore, it is highly plausible that the tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin is an allegory about a lokator showing up at the town of Hamelin and recruiting much of the town’s youth to settle out further east.

To substantiate this story, historians of the tale of the Pied Piper have studied surnames that appear within and around the town of Hamelin in the thirteenth century and found incidences of the same surnames appearing further east around the Baltic Sea region.

This would seem to suggest a significant emigration from Hamelin to Eastern Europe and the Baltic Sea region at some time in the Late Medieval period.

Thus, the most likely eventuality is that the tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin is an allegorical story about a lokator recruiting over a hundred young people from Hamelin to colonize the Baltic Sea region.

Whatever the actual truth, we know what the resonance of the tale has been. It became widely popularised during the folk-myth revival of the nineteenth century when writers such as Robert Browning and the famous Brothers Grimm republished editions of the story.

As a consequence, it has become widely known to modern people. The tale today is legendary. It has even given a name to a popular saying throughout the Anglophone world; “He who pays the piper plays the tune.”

Sources

Helen Zimmern, The Hanseatic League (London, 2017); Michael Pye, The Edge of the World: How the North Sea Made Us Who We Are (London, 2015).

Trevor Dickinson, ‘The Pied Piper of Hamelin’, in The School Librarian, Vol. 60, No. 1 (Spring, 2012), p. 37; D. L. Ashliman (ed.), The Pied Piper of Hamelin, and related legends from other towns (Pittsburgh, 1997); Radu Florescu, In Search of the Pied Piper (London, 2005).

Wolfgang Mieder, The Pied Piper: A Handbook (Westport, Connecticut, 2007); Robert Browning, The Pied Piper of Hamelin (London, 1842); Clyde de L. Ryals, The Life of Robert Browning: A Critical Biography (London, 1993).

Good pߋst. Ι absolutely love this site. Keep it up!