After the October Revolution, Soviet leadership inherited a nation in shambles after a costly World War. Faced with an economy that had been backward before the war and a civil war taking shape, policy became focused on the modernization of the USSR to improve the labor productivity that had already dropped to one-third of pre-war levels. Scientific management, or Taylorism, was put forth as a possible solution to the USSR’s economic woes and garnered the support of party stalwarts such as Lenin and Trotsky. Despite strong support from the top, Taylorism was plagued with many setbacks. Due to these numerous obstacles, Taylorism in the USSR was never static and consistently evolved in an attempt to meet the changing factors that blocked its path. Despite Taylorism’s proponents’ efforts, it failed to gain a firm footing in the USSR. Soviet culture, ideology, and politics blocked Taylorism at every turn, leading to its eventual decline.

Alexsei Gastev, known as the “father of Soviet Taylorism,” initiated the first attempt to implement Taylorism in the USSR in 1918. As a secretary of the Russian Metalworkers Union, Gastev introduced the use of progressive piece rates, which was a central component of Taylorism. Despite success with the metalworkers, in December 1917, the print workers union had beat him to the punch and passed a resolution against piece rates, which were still highly unpopular since Czarist Russia had first introduced them to select industries. Railroad workers followed in January 1918, denouncing piece rates believing they would lead to unemployment and physical exhaustion. By March 1918, the issue had exploded into controversy, and a meeting between trade unions and government officials was called. At the conference, the metalworkers put forth a platform calling for labor discipline and an end to democratic labor practices. Opponents were outraged what they saw as a restoration of capitalism. Lenin came to the aid of Gastev calling for a resolution on the side of the metalworkers union. Contrary to his wishes, the chairman passed a resolution that looked more like a compromise, essentially leaving the question up to the trade unions, which had already come out against it.

Lenin had not always been an advocate of Taylorism. As early as 1913 he had come out against Taylorism as a system of “sweating in accordance to all the precepts of science.” Under this system, “the capitalist obtains an enormous profit, but the worker toils four times harder as before and wears down their nerves and muscles four times as fast as before.” After studying works by Frank Gilbreth and Frederick Taylor, he had a sudden change of heart. By 1918 Lenin reconciled Marxism with Taylorism, emphasizing that “the possibility of building socialism depends exactly upon our success the Soviet Power and the Soviet organization of administration with the up-to-date achievements of capitalism.” Lenin shared a fair share of the controversy Taylorism was stirring up in the USSR. In response to his article in Prada, “The Immediate Task of the Soviet Government,” O.A. Yermanskii, a Menshevik and critical player in the anti-Taylorist movement, published a critical response. Drawing on his experience in the Russian Technical Society and citing labor studies conducted by Edgar Atzler in Germany, Yermanskii denounced Taylorism as hazardous to workers’ health, due to the excessive expenditure of energy.

Gastev and Lenin’s initial hope for quick implementation of piece rates was dashed by a strong opposition that was only getting stronger. This marked the beginning of a period of years where scientific management would be consistently on the defensive. Despite a discouraging start, these were the formative years of Gastev. While working in the metalworker’s union, he began to develop ideas on a distinctly Soviet form of Taylorism. For Taylorism to succeed, he believed there could be nothing short of a complete cultural revolution. Gastev divided workers into five groups based on skill levels, focusing on the group whose tasks were already completely standardized as a model for the future Standardization would eliminate the creative labor at the top and the unskilled at the bottom. He argued that this group would be the forerunners of a culture where “uniformity would permeate every aspect of the worker’s existence.” Everything from a worker’s name to his sex life would be defined technically.

Gastev’s version of future proletarian culture provoked further controversy over the implementation of Taylorism in the USSR. Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We was a scathing attack from the Soviet literary world on Gastev and Taylorism in general. Another notable opponent was A.A. Bogdanov, a Soviet science fiction writer, the leader of the Proletarian Culture (Proletkult) movement, and a noteworthy opponent of Taylorism before the revolution. Bogdanov saw the progression of proletarian culture in the direction of greater individuality, where every worker would be a “creative machinist.” Regarding other aspects, Bogdanov believed Taylorism would lead to two adverse outcomes: the creation of a worker aristocracy and the mental atrophy of workers from the constant repetition of movements. Attacks on the concept of a worker elite would be an essential rallying point for ideological opponents as the debates progressed.

If anything, due to the egalitarian nature of a state populated by one type of worker, Gastev’s new proletarian culture should have discounted accusations over the creation of a new worker’s elite, but this was not the case The majority of Taylorism’s advocates were engineers who saw themselves as playing a crucial role in its implementation. Simultaneously, one of Gastev’s proteges, A.Z. Gol’tsman, was directly advocating the creation of a worker aristocracy. Even more damning was Lenin’s resolution at the First All-Russian Congress of Sovarnakhozy in 1918, which brought in thousands of pre-Revolutionary bourgeois specialists into management functions. Lenin hoped that bringing in specialists would help train Communist managers. This resolution created an uproar in the factories, pitting the red directors, who were former workers, against the new specialists, and consequently against Taylorism as a whole. Realizing that such an ambitious, and therefore controversial, platform did not help the cause of Taylorism, Gastev was forced to tone down the rhetoric.

Despite alienating influential party members such as Bagdanov, Gastev gained the support of Leon Trotsky. Trotsky combined Taylorism and labor discipline, stating that “if you take militarism, then you’ll see that in some ways it was always close to Taylorism.” At the Ninth Party Congress in 1920, Trotsky put forth a platform to end trade union management and to forcefully impose labor discipline on workers. This was the first time an organized opposition, the Democratic Centralists, came out against Trotsky and Taylorism. Composed primarily of red directors and trade union leaders, they denounced Trotsky’s program. They brought the issue of a worker aristocracy to the foreground once more with a scathing attack on Gol’tsman. Initially, Lenin had supported Trotsky’s platform, but with the unified Democratic Centralists creating an uproar, it became politically dangerous to continue doing so. Lenin took the middle ground, advocating Taylorism as a managerial, rather than disciplinary strategy. To the dismay of many, Lenin did advocate and succeed in the abolishment of collective management, emphasizing the importance of skilled managers.

Though the Democratic Centralists had created a significant roadblock for labor militarization by forcing Lenin to back down, Trotsky was not phased by the opposition, and later in 1920 continued to fight for it. After some persuasion, Trotsky was put in charge of the People’s Commissariat of Railroads in August 1920. Seeking to circumvent the trade union opposition, Trotsky went over their heads and formed Tsektran, a parallel trade union committee. Trade unions met this high-handed action with outrage, putting Tsektran in the center of a growing controversy. Despite Trotsky’s efforts, it soon became apparent that there was a split within Tsektran. Several members, including Gol’tsman, called for the immediate implementation of Taylorism, while some engineers realized that this was impossible. This illustrates a reoccurring case in the history of the USSR, where ambitions could never meet reality.

Tsektran was successful in temporarily deflecting the opposition, but it quickly backfired on Trotsky. Zinoviev, a prominent member of the Central Committee and a soon-to-be member of the Politburo, joined the trade unionists in denouncing Tsektran. In response, Trotsky called a conference to discuss the issue of Taylorism in regards to railroads. Events spiraled out of control, and the conference was expanded, allowing a higher number of opponents to attend. In January 1921, the First All-Russian Conference on the Scientific Organization of Labor convened in Moscow. To Trotsky’s dismay, the majority of the proceedings were spent primarily discussing the benefits and detriments of Taylorism. The conference split into two different camps, with Gastev speaking for the Taylorists and Yermanskii coming forward to speak for the anti-Taylorists. Gastev was close to scoring a decisive victory for Taylorism through a decree establishing the hegemony of his recently founded organization, the Central Institute of Labor (TsIT), overall other organizations dedicated to the scientific organization of labor (NOT). At the last moment, after pushing the resolution through the preliminary stages, it was squashed. By the end of the conference, it was apparent that the two opposing sides were too polarized to reach any meaningful solution, and the second conference was called for in the future. The raging battle over labor militarization and Taylorism manifested in open revolt in February 1921.

Transportation workers staged strikes in Petrograd, bringing the city to a standstill, and in response, sailors in the Kronstadt fortress openly rebelled. As the events unfolded, some Taylorists, including Gastev, felt the need to be more cautious. This group believed that Taylorism needed to be introduced gradually from the lowest levels, considering that the results would win the support of workers and managers. Others denounced this practical approach, marking a split within the Taylorists into what historian Zenovia A. Sochor has deemed the “ideologues” and the “pragmatists.”

As the head of the “pragmatists,” Gastev took a cautious stand in voicing his opinion. Rather than letting Taylorism once again bog down in ideological debates, Gastev chose to leave ideological matters in the hands of the government. Realizing that Lenin was firmly behind Gastev, this was an intelligent move, for ideologically, the party would always come on the side of him. He intended to implement Taylorism in a case-by-case basis, focusing on areas that needed it most, rather than attempting to make sweeping changes. What Gastev did not account for was how far the “ideologues,” led by Platon Kerzhentsev, were willing to go to wrestle control of the movement from his hands. Kerzhentsev advocated a broader application of Taylorism, fixing set standards across all industries. Beyond this, Kerzhentsev envisioned the application of Taylorism in every aspect of society from the army to the schools.

In 1923 Kerzhentsev and the “ideologues” founded Liga Vremya (Time League) in response to Gastev’s TsIT. Contrary to the TsIT’s attempts to gain the support of a small, highly trained group of workers, Liga Vremya used agitational techniques to gain a broad base of support both for Taylorism and against the TsIT. Kerzhentsev hoped to bring Taylorism out of the confines of workshops to the masses. Using an appeal for a “struggle for time,” which to them meant a struggle against wasting time, Liga Vremya’s membership exploded to close to 25,000 members in 1924. Though Liga Vremya succeeded in generating membership, it failed in organizing it. Regionally, each cell differed in their actions, with some waging press campaigns and others trying to implement Taylorism through actions such as penalizing workers for lateness. Overall, Liga Vremya did for more to hurt than to help Taylorism. By attacking the TsIT, they were attacking the only organization that was conducting valuable research. Furthermore, their narrow focus on the theoretical over the practical aspects of Taylorism doomed Liga Vremya to impotence.

In 1924 the much delayed Second All-Russian Conference on NOT was finally convened to sort out the ideological tangle that had developed. Kerzhentsev and Gastev both put together pro-Taylorist platforms, and Yermanskii returned to attack Taylorism. Once more, the conference broke into petty conflicts. Gastev denounced the organization of the conference as inherently unfavorable for the “pragmatists.” Kerzhentsev descended into communist rhetoric, demanding the taking of the movement form a “petty bourgeois,” like Gastev, and putting it back in the hands of the movement to real communists. Eventually, Valerian Kuybyshev came down firmly on the side of Gastev and the TsIT, ending the ideological struggles that had retarded the implementation of Taylorism since the beginning.

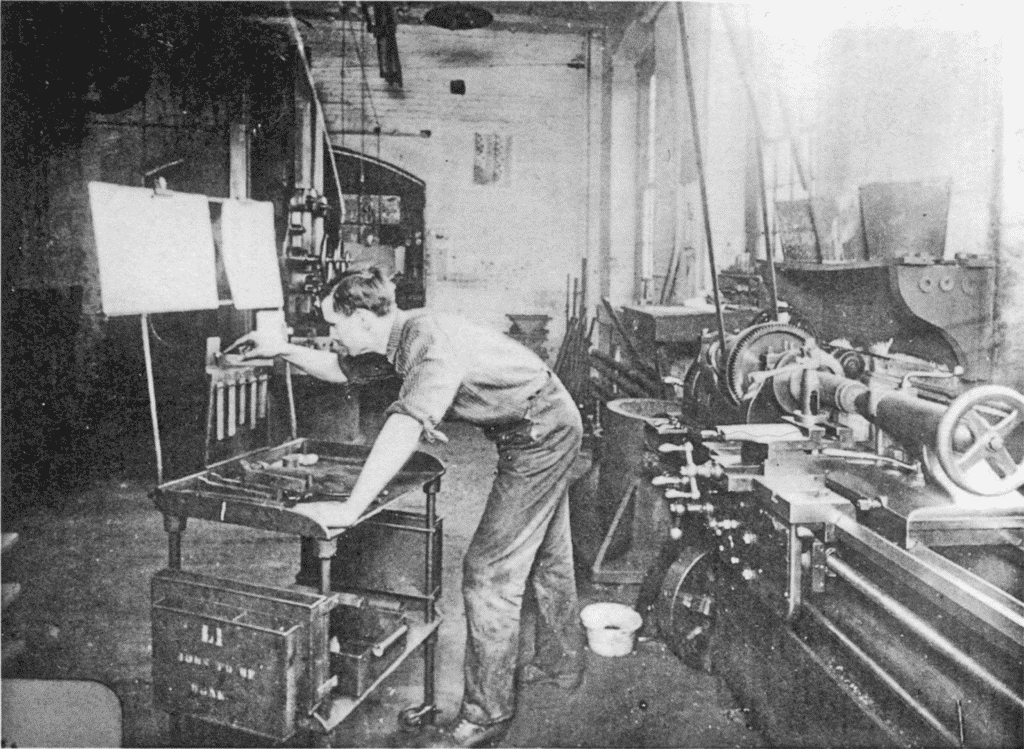

Winning the ideological battle did not end Gastev’s struggle. Ideological backing mattered little when it came down to introducing Taylorism on the factory floor. Workers were untrained and undependable when it came to work. Most did not even own clocks and arrived based on seasonal changes. How could a movement dedicated to the effective use of time hope to succeed if their workers could not even arrive to work at a consistent time? Topping this off was the lack of qualifications common among most Russian workers who were woefully ignorant of most technical matters. Work ethic was another glaring problem. Lenin said, “The Russian is a bad worker compared with people of advanced countries. It could not be otherwise under the czarist regime and in view of the persistence of the hangover from serfdom.” Gastev himself reflected on the Oblomov mentality of the Russian worker, who lazily waited for technology to solve his woes and end the need to work. Some such as Preobrazhensky made the unfair statement that the lack of work ethic was a symptom of the Russian National Character. While untrue, this statement illustrates the pervasive problem of labor productivity that faced Taylorists and the USSR in general. Taylorism was a hopeless cause if every worker was unskilled and unproductive.

Managers and engineers proved to be extremely ineffective, as well. Some, such as pre-bourgeois specialists, did support and attempted to implement Taylorism, but as was mentioned, the workers proved to be an enormous obstacle. Others who supported it, but weren’t specialists, had little education on the matter and failed to implement it successfully. Combined with this issue was a general lack of initiative among managers and engineers. Politically, it was much safer to do nothing at all, rather than risk the wrath of the party. Failure could mean life or death in many cases. Finally, a large number of managers were staunch opponents of Taylorism. Red directors held many key management positions and prevented the implementation of Taylorism in their factories. When consultants on Taylorism came into factories, they were met with open hostility or skepticism. Consultants went unpaid unless they could prove tangible results, which was difficult. If results could not be verified, many were taken to court. In some cases, proponents of Taylorism were met by violence, as workers drove them out by force or seized entire factories to prevent them from entering.

Party members were far more willing to support Taylorism, but did not understand it well enough to push for successful implementation. The most challenging portion to grasp was the comprehensive nature of Taylorism, which required application at every level of production to reach its full potential. Instead, managers implemented it piece by piece, pushing for speed-ups in certain sections, which in turn created bottlenecks further along the production process. In these cases, the implementation of Taylorism resulted in far more significant labor shortages than the traditional methods used by factories. These problems were compounded by a dichotomy between party expectations for production and what was possible. Enormous quotas were put forward that was next to impossible to meet. To meet them, workers worked at obscene paces, damaging machinery through incorrect usage and as a result created shoddy goods.

Political organization and action proved to be a further problem for the implementation of Taylorism. Despite the support the TsIT had received since its inception, the government failed to provide its research with adequate funding. An observer from the Taylor Society, S. Slonim, remarked on the situation: “These efforts are at present crude–for want of proper equipment some experimental machines are being made of wood! But the mental attitude seems sound; it is scientific and its motive is the regeneration of Russian industry.” This gap between action and ability was a crucial factor in the institute’s ineffectiveness. The lack of funding had further consequences for other organizations, creating a ripple effect through the NOT community. With the TsIT’s inception in 1920, it was granted authority in coordinating a number of provincial organizations on NOT. To affirm this, a conference was called among all the organizations in December 1921. Therefore, the Secretariat of Institutes Studying Labor (SUIT) was formed as the coordinating arm of the TsIT. It was agreed that the SUIT would handle all funding of the provincial organizations. This posed a problem since the SUIT lacked any funding of its own. As a result, there was no money requested for any of the provincial organizations, causing many of them to shut down.

Monetary issues aside, political bodies failed to organize well enough for NOT to succeed. Campaigns were launched to generate support for NOT, but their results were minimal. Voluntary economic commissions to discuss NOT were set up in factories, but attendance was low. The Orgburos were a notable attempt, that would have possibly worked if not for the chaotic Soviet bureaucracy. After a circular released in 1923, the Orgburos first emerged as organs for each factory under the People’s Commissariat of Worker and Peasant Inspections (NKRKI). By 1925, they were deemed the fundamental unit of implementing NOT within Soviet industry. Theoretically, the Orgburos should have had enough authority to rationalize the factories, but the NKRKI did not have a direct line of authority over the managers, who instead reported to local party officials. Realizing this issue would be the death-stroke of the Orgburos, the NKRKI appealed the issue unsuccessfully. Without any means of enforcement, the Orgburos were at the mercy of the managers. In some cases, projects were implemented if the manager was a proponent of Taylorism, but usually, managers did everything in their power to prevent the Orgburos from functioning. Some managers loaded the Orgburos down with paperwork; others interestingly shut them down in the name of “rationalizing” production. These problems were finally addressed in 1928, when Taylorism’s heyday was coming to a close in the USSR.

A study done in 1927 by the International Labour Office released findings that Taylorism, despite enormous support, had failed in escaping the confines of the workshop into the economy. One year later Stalin stated that technology and practices should not be imported from the West, and thus cut off the government support that the Taylorists had taken for granted during the last decade. 53 engineers in the town of Shakhty were arrested and brought to trial as wreckers and saboteurs. This marked the beginning of a campaign against pre-bourgeois specialists and those who advocated rationalization. By 1931 around 7,000 engineers and specialists had fallen victim to this purge, with an enormous percentage of them being Taylorists. Gastev himself managed to survive longer, due to the support of top party members still in Stalin’s favor, but eventually fell victim to the purges in 1939.

Taylorism in the USSR is not an unique phenomenon in that it failed despite enormous levels of support. This was true in many cases, with Stalin’s collectivization and centralization being examples that come to mind. Support from the top was met with dissidence or inability from the bottom and mid levels. Compounding this problem was the cluttered, overlapping political structure, which prevented orders from the top from being implemented. S. Slonim best encompasses the dichotomy between implementation and ambition between 1918 and 1928: “The only difference between the “but” of today and the “but” of czarist times, is that in czarist Russia they could but they wouldn’t, and in Bolshevik Russia they would, but they couldn’t.” Rationalization was replaced with centralization until Kruschev came to power, providing more fertile grounds for it to take root in.

Sources:

Bailes, Kendall E. “Alexei Gastev and the Soviet Controversy over Taylorism, 1918-1924.” Soviet Studies 29 (1977).

Bedeian, Arthur and Carl Phillips. “Scientific Management and Stakhanovism in the Soviet

Union: A Historical Perspective.” International Journal of Social Economics 17 (1933).

Bessinger, Mark. Scientific Management, Socialist Discipline, and Soviet Power. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Devinat, Paul. Scientific Management in Europe. Geneva: International Labour Organisation, 1927.

Gilbreth, Frank B. Primer of Scientific Management. Easton: Hive Publishing Co., 1973.

Hughes, Thomas. American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm. New York: Penguin Books, 1989.

Lenin, V.I. “A ‘Scientific’ System of Sweating.” In Lenin Collected Works 18, translated by

Stepan Apresyan. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975.

Lenin, V.I. “The Immediate Task of the Soviet Government.” In Lenin Collected Works 27,

translated by Clemens Dutt. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1972.

Lenin, V.I. “The Taylor System – Man’s Enslavement by the Machine.” In Lenin Collected Works

20, translated by Bernard Isaacs and Joe Fineberg. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1972.

Johansson, Kurt. Aleksej Gastev: Proletarian Bard of the machine Age. Phd Diss, University of Stolkholm, 1983.

Peci, Alketa. “Taylorism in the Socialism that Really Existed.” Organization 16 (2009).

Slonim, S. “Russian Scientists in Quest of American Efficiency.” In Classics in Scientific Management, ed. D. Del Mar and R.D. Collins. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

Sochor, Zenovia. “Soviet Taylorism Revisited.” Soviet Studies 33 (1981).

Stalin, Josef. “Speech of J. Stalin.” In Labor in the Land of Socialism, edited by A. Fineberg.

London: M. Lawrence, 1936. Quoted in Bedeian, Arthur and Carl Phillips. “Scientific

Management and Stakhanovism in the Soviet Union: A Historical Perspective.”

International Journal of Social Economics 17 (1933).

Suny, Gergor. The Soviet Experiment: Russia, The USSR, and the Successor States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Trotsky, Leon. Sochineniia 15. Moscow: Gosizdat, 1927. Quoted in Bessinger, Mark. Scientific

Management, Socialist Discipline, and Soviet Power. Cambridge: Harvard University

Press, 1988.

Yermanskii, O.A. Sistema Teilora. Quoted in Bessinger, Mark. Scientific

Management, Socialist Discipline, and Soviet Power. Cambridge: Harvard University

Press, 1988.

- Tulip Mania – The Story of One of History’s Worst Financial Bubbles - May 15, 2022

- The True Story of Rapunzel - February 22, 2022

- The Blue Fugates: A Kentucky Family Born with Blue Skin - August 17, 2021