Last updated on March 8th, 2023 at 05:45 am

Cold War tensions between the USSR and the United States hit an all-time high during the 1960s. Events like the Cuban Missile Crisis and the building of the Berlin Wall were just a few examples of how extreme things were.

In Asia, North, and South Korea were only a decade past the terrible Korean War that tore through the peninsula. To the North, Kim Il-sung, the revolutionary dictator and founder of Communist North Korea ruled a hermit kingdom.

In the South was a US-backed dictatorship, propped up by a sizeable US military presence. It’s here that the fascinating story of US defector Charles Robert Jenkins played out.

Charles Robert Jenkins Defects to North Korea

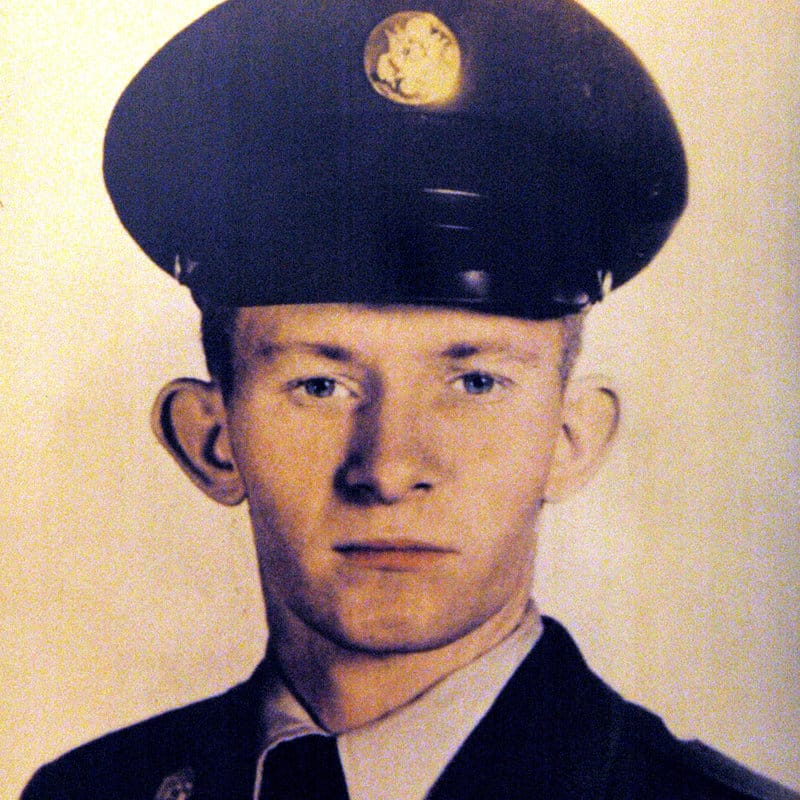

Born in 1940 in Rich Square, North Carolina, Charles Robert Jenkins joined the National Guard at fifteen and then the army in 1958. He served a deployment in South Korea in 1960 and in 1964, he was deployed a second time. He was one of the many US soldiers stationed at the DMZ between North and South Korea.

During this time, the Vietnam War was quickly escalating. For many soldiers, serving in Vietnam felt like an inevitability. The grim prospect terrified many soldiers like the 24-year-old Charles Robert Jenkins.

As he became more anxious, he put together a risky plan to avoid deployment to Vietnam which would put him in North Korea for almost the rest of his life.

One night, Charles Robert Jenkins was on a typical nightly patrol along the border. While passing through some woods, Jenkins said he heard a sound and ordered his troops to halt while he checked it out.

When he never returned, they sounded an alarm, and a massive search went underway. When nobody found him, it wasn’t far-fetched to assume North Korea snatched him. It wouldn’t be the first case of North Korea abducting a foreign soldier or citizen.

Most wouldn’t know the truth of what happened that night until decades later. It wasn’t an abduction like everyone feared, and Jenkins wasn’t investigating something in the woods. He rushed through the woods, stumbling across North Korean soldiers who were extremely surprised to see him. After surrendering his weapon, they took Jenkins into custody.

After the Defection

When the search found no clues about Charles Robert Jenkins’s whereabouts, the US Army decided that he likely defected after reading his mail.

Several weeks later, a Pyongyang propaganda broadcast claimed that a US serviceman defected due to horrible living conditions in South Korea. The US military and media were quick to make the connection to Charles Robert Jenkins.

As you can guess from the modern treatment of deserters like Bowe Bergdahl, the government and press were not too happy. The media tore him apart, reporting that he had written at least four letters home laying out his plans, though there isn’t any record of them today.

Despite the government’s claim, Jenkin’s mother and friends adamantly defended him. Sadly, they would never see him again. Nobody heard much about Charles for the next four decades, until 2002 when a curious turn of events got Charles out of the country.

Charles Robert Jenkins’ Time in Captivity

The thing that makes this story fascinating is that of the six known servicemen who defected to North Korea after the war, Jenkins was the only one to make it out of the country alive.

Upon release, Jenkins gave several interviews telling his story before and after he defected. In a Washington Post interview, Jenkins spoke of his naivety at the time. His original plan was to defect to North Korea and then get asylum in the Soviet Union.

Sadly, things didn’t work out like that, and he immediately regretted his escape. Instead, he spent decades in what he described as a prison state that nobody could escape.

From his arrival until 1972, he was confined in a one-bedroom home with fellow deserters Jerry Parrish, Larry Abshier, and James Dresnok. The house had no running water, and they were subjected to regular beatings by their guards.

Their free time was spent studying and memorizing the Juche, the communist philosophy of Kim Il-sung. On top of that, they faced malnourishment and other forms of psychological torture. On several occasions, guards forced Jenkins to dig his own grave.

At one point, he and a few other deserters managed to make it to the Soviet embassy in Pyongyang, hoping for asylum. The embassy returned them to North Korean authorities.

A small amount of freedom

Seven years after defecting, Jenkins received his own home and a small amount of freedom. The government still kept him under constant watch, but he at least wasn’t trapped in a one-bedroom house with three others. That’s not to say his life was great. North Korean winters are harsh, and his home had no heat. Additionally, food scarcity was common because of the famines that consistently rocked the country, so he was malnourished.

The main reason they kept Charles Robert Jenkins alive was that he was useful. That doesn’t mean they had to treat him well.

During an interview for North Korean television after his release, he rolled up his sleeves and accidentally exposed a tattoo he got while serving in the US army. Doctors came in the same day and forced him down. They removed the tattoo without anesthesia using scissors and a scalpel.

North Korea didn’t keep Charles Robert Jenkins alive just because he spoke English. The lack of Americans in the country made him invaluable as an actor in propaganda films, which Pyongyang was churning out regularly. Jenkins acted in roles like an “evil American spy” in over twenty films.

Falling in love

For years, people suspected that North Korea was abducting foreign citizens, particularly from Japan. From 1977 to 1983, at least seventeen are confirmed. A Japanese nurse named Hitomi Soga and her mother were two of those abducted.

There is no record of what happened to the mother, but we know North Korea forced Hitomi Soga to live with Charles Robert Jenkins and teach Japanese to the North Korean military.

The government wanted to breed children with Western features as spies, so they forced them to marry and sleep together. Other defectors found themselves in similar arranged marriages.

Despite the circumstances, Charles R. Jenkins and Hitomi fell in love. This marriage eventually allowed Jenkins to escape.

Leaving the country

In 1994, Kim Il-sung died of a heart attack. His son, Kim Jong-il, replaced him. Kim Jong-il’s approach was less isolationist than his father’s, and he attempted to normalize relations with Japan in 2002. He admitted to the abductions of Japanese citizens and allowed the five who were still alive to visit their families in Japan briefly.

Hitomi flew back to Japan shortly after. Instead of returning them, the Japanese government began negotiating to return the abductees’ families.

Initially, Jenkins stayed in North Korea with his daughters. Years of trauma made him believe that they were testing his loyalty. Even if he could leave, he was afraid that the US military would arrest him the second he arrived in Japan.

In 2004, Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi visited Jenkins in Pyongyang, where Jenkins again refused to leave North Korea. It wasn’t until later that year that he finally consented to leave the country to receive medical treatment in Indonesia.

Though it was initially supposed to be a short trip, his wife and daughters convinced him to risk the US court-martial and stay in Japan. In July of 2004, Jenkins turned himself in at a US military base near Tokyo.

A few months later, Charles Robert Jenkins’ trial began. In a stroke of luck, the US military wasn’t feeling particularly punitive and sentenced him to 30 days in jail. After his release, Jenkins was free for the first time in forty years. He and his wife settled on her home island of Sado, off the west coast of Japan, where he lived until he passed away in December 2017.

For more on the amazing life of Charles Robert Jenkins, read his book The Reluctant Communist: My Desertion, Court-Martial, and Forty-Year Imprisonment in North Korea